Well, at least I learned something

I was all set to write this post Saturday on how the Constitution's Article 2, Section 2, states that the President has to seek the advice and consent of the Senate on nominating and appointing Supreme Court justices.

I had read Article 2, Section 2, Clause 2 of the Constitution several times recently and at my reading comprehension level, it seemed plain to me that a President has to seek both 'advice and consent' on not only Supreme Court justices but "Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and all other Officers of the United States", also. Here's Article 2, Section 2, Clause 2;

He (The President) shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur; and he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law: but the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.

Regardless of how many times I read Clause 2 it wasn't totally clear to me if the president needed 'advice' from the Senate on nominating justices of the Supreme Court and 'other officers' or not, so I decided to see what James Madison, the "Father of the Constitution", had said or done about this clause and came up with three nominations, one for Secretary of State, one for Secretary of War (that's now Secretary of Defense) and one to the Supreme Court. Although the rejection of Madison's Supreme Court nomination, Alexander Wolcott was rejected at the 'consent' level, you still get the idea that Madison was, if anything, respectful of the Senate's role in the process, which included seeking their advice on nominees.

1809: President James Madison dropped plans to appoint the Swiss-born Albert Gallatin, Thomas Jefferson's secretary of the Treasury, as his secretary of State in the face of Senate opposition. Madison kept Gallatin at Treasury and gave the State Department job to a senator's brother, Robert Smith

1811: The Senate rejected Alexander Wolcott, a Madison nominee to the Supreme Court and customs collector from Connecticut, on the grounds that he lacked the experience and temperament for the job.

1815: Madison nominated Henry Dearborn, a former secretary of War under Jefferson and general during the War of 1812, to run the War Department again. Madison sought to withdraw the nomination the next day after quickly realizing how little support there was for Dearborn. The Senate had already voted to reject Dearborn, but had the vote erased from its journal.

I had also heard and read recently of how Bill Clinton, who had a Democrat majority in the Senate still sought the 'advice' of Orrin Hatch, the Senate minority leader on the Judiciary Committee, before nominating Ruth Bader-Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer. Clinton had wanted to nominate his Secretary of Interior and former Arizona governor, Bruce Babbitt but after seeking the advice of MINORITY leader Hatch, he showed class and statesmanship by accepting Hatch's recommendations. Here is what Orrin Hatch later wrote in his autobiography:

[It] was not a surprise when the President called to talk about the appointment and what he was thinking of doing.

President Clinton indicated he was leaning toward nominating Bruce Babbitt, his Secretary of the Interior, a name that had been bouncing around in the press. Bruce, a well-known western Democrat, had been the governor of Arizona and a candidate for president in 1988. Although he had been a state attorney general back during the 1970s, he was known far more for his activities as a politician than as a jurist. Clinton asked for my reaction.

I told him that confirmation would not be easy. At least one Democrat would probably vote against Bruce, and there would be a great deal of resistance from the Republican side. I explained to the President that although he might prevail in the end, he should consider whether he wanted a tough, political battle over his first appointment to the Court.

Our conversation moved to other potential candidates. I asked whether he had considered Judge Stephen Breyer of the First Circuit Court of Appeals or Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg of the District of Columbia Court of Appeals. President Clinton indicated he had heard Breyer's name but had not thought about Judge Ginsberg.

I indicated I thought they would be confirmed easily. I knew them both and believed that, while liberal, they were highly honest and capable jurists and their confirmation would not embarrass the President. From my perspective, they were far better than the other likely candidates from a liberal Democrat administration.

But, although James Madison and Bill Clinton showed diplomacy and statesmanship with their willingness to seek the Senate's advice on nominating, what is the correct interpretation of Article 2, Section 2, Clause 2?

The answer comes from a Supreme Court ruling from 1804, ironically titled, Marbury v. Madison. Yes, 'Madison' is James Madison, who in 1804 was Thomas Jefferson's Secretary of State. Although Marbury v. Madison was not about nominating justice to the Supreme Court (William Marbury sued Madison, and won to force his holdover appointment from the John Adams' presidency to Washington D.C. justice of the peace) it does have one very clear and unambiguous statement in it's ruling.

1. The nomination. This is the sole act of the president, and is completely voluntary.

So, my interpretation was wrong. Bush is not constitutionally required to seek the 'advice' of the Senate on his nominees to the Supreme Court.

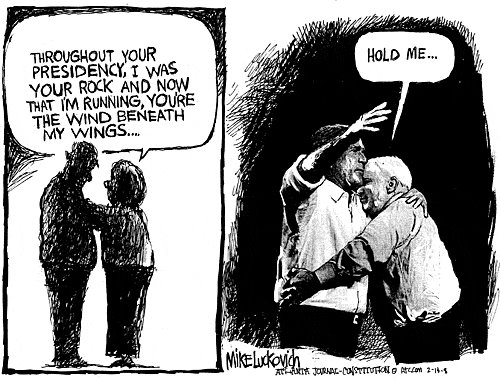

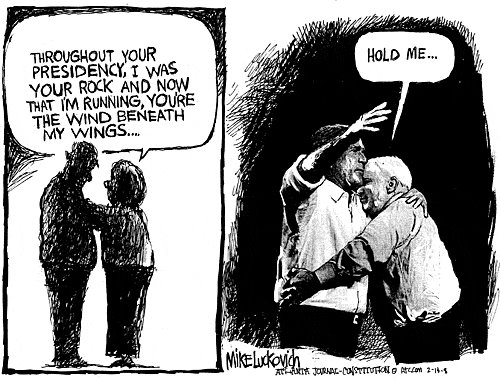

And just because Madison and Clinton showed both class and statesmanship when they nominated their justices-we know we won't get that now from the most secretive, most narrow-minded and most divisive president in history. Sure, Bush has called Judiciary Committee's minority leader, Patrick Leahy, but we'll see how much of his advice he takes.

Senate Democrats will be prepared to do battle.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

This blog is not required reading.

War Criminals

Blog Archive

-

▼

2005

(175)

-

▼

July

(25)

- OH... THAT TESTIMONY?

- CAFTA

- PROGRESSIVE THOUGHT WINNING OUT OVER CONSERVATIVES

- Guest Post - Political Party Strength

- Guest Post - List of Political Parties In The Unit...

- SEPARATION OF CHURCH & STATE

- GIVE HIM A PASS

- GUMPSPEAK

- FROM THE HORSE'S MOUTH

- REPUBLICANS vs. THE FACTS

- SHE'S FINALLY PISSED ME OFF!

- ADVICE AND CONSENT

- Time for a 'Frog March'

- MEASURE

- AIDING OUR ENEMIES

- THE COST OF DIVERSION

- HOW DO YOU BURP A " . " ?

- HARD WORK

- MILLER JAILED-COOPER WALKS

- "TRUTH TOUR"

- INDEPENDENCE DAY

- A FREE PRESS vs. JUSTICE

- SANDRA DAY O'CONNOR

- ARTICLE. II. SECTION. 2.

- U.S. TROOPS HELD CAPTIVE BY TALIBAN

-

▼

July

(25)